In the various interactions I’ve had with ChatGPT, and the various posts and articles I’ve read by other people, I’ve had this recurring thought – talking to ChatGPT is like talking to a gifted child.

AI often makes me think of a child because we need to teach it about the world so that it can flourish there. But ChatGPT has refined my impression further.

To me, ChatGPT is like a precocious and gifted alien child.

It appears to have incredible skills that dazzle you, but yet it doesn’t know some of the most basic stuff about the world we live in. As you speak to it, you ask it questions and it occasionally says wonderful things, but you’re not sure why it says them, whether what it says is true, or whether what you say is teaching it. It could have come from Mars.

We’d expect to have some influence over a person we communicate with. That would be normal – to be able to influence the person you talk to. But when the data is crowdsourced, you have to hope that everyone else who talks to this AI is going to improve it and not make it worse.

ChatGPT is this unfathomable being who veers between incredibly lucid insights and occasionally bizarre nonsense.

Would you employ that person? Would you want them as the spokesperson for your brand? The one who deals with your customers every day? Probably not.

As fantastic as it is, there’s risks attached to using ChatGPT and large language models (LLMs) in general for businesses. Here are just some of the risks we’ve considered so far:

Data

Where does it get data from? Does it take what people say to be absolute truth? That’s horribly dangerous. Consider situations where there’s an angry mob generating most of the online discourse on a topic, or when a government carefully monitors the public discourse so people would only express the ‘accepted truth’ online and the ‘actual truth’ when they’re absolutely sure nobody and no device is listening? In that last case, the LLM becomes a political tool that influences the masses on the state-approved version of truth.

Who processes your data, and where is it processed? If customer data is sent to an LLM there’s a legal risk. According to GDPR, any instance of that customer data has to be deleted when the customer requests it. How can you do that when a third party (such as OpenAI) has that data? It’s your responsibility, if you’re providing the service to the customer. Do you even know what an LLM would do with customer data, where it’s stored, or who sees it?

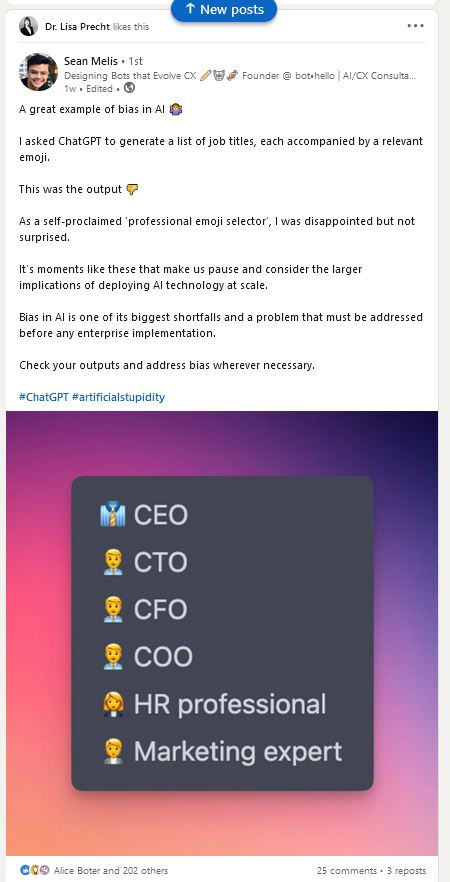

Bias

What biases are in the data and the algorithms? When you don’t know what data has been used to train it, or how it will interpret that data, you can’t be sure what biases ChatGPT has. The results can distort reality. Here’s a great example of that:

Lies

Can it give correct advice every time it’s asked? We’ve seen bots that recommend a patient kill themselves (this was GPT-3 in 2020). LLMs don’t know truth from fiction – they only know what people tell them to know or, in the case of ChatGPT, what it decides to generate.

Off brand messaging

How much control over your brand’s values, messaging and persona do you have when you let an LLM generate the content? Of course, you can train an LLM on content written in your brand voice, but you can’t police everything it says all the time. What if, like we’ve seen with Alexa in the past, it offers information or advice that you don’t agree with or that could damage the brand? You wouldn’t hire just anyone to do your branding because it could ruin your reputation, so why would you hire this gifted little alien to do it?

Moderation (humans in the loop)

Has this ‘magical’ tool required vast teams of low-paid workers to make it workable? This is the dystopian element of the AI industry. Rather than having automated bots that do our unwanted tasks, we occasionally have automated bots that require low-paid workers to help them do their job. In this case, it’s tagging extreme online content. It has recently been discovered that OpenAI outsourced moderation of its tool to workers in Kenya, many of whom were earning under $2 per hour. Some report that an average Kenyan wage is $1.25 per hour, though Apple and Amazon have come under fire in the past for underpaying workers.

Competition

If it becomes an arms race, will we remember the customer’s needs and their rights? As one vendor implements large language models into its software, so another copies. Then, another adds it, and then another – they all want to keep pace with innovation. But merely keeping pace is not enough. They need to compete and outdo one another. So, vendors go further, trying to be bolder than their competitors with this shiny new toy. This could potentially turn into an arms race for who has superior integration of LLMs into their platforms and capabilities. When everyone asks ‘who’s pushing the boat out more?’ the risks and ethics of it all could potentially get lost in the noise while everyone races for market share.

Copyright

Who owns the output? It may seem you can re-use the materials generated by ChatGPT without paying for them. Who knows what could happen with generative AI though? What if a hit pop song is created, or a work of art by AI sells for a huge sum at auction, or a bot becomes a famous personality? What about this book. Who owns it? The person who crafted the prompt, or the company that owns the algorithm?

Who owns the input? It also may seem like content generated by ChatGPT (and other generative AI models) is entirely new and unique. But don’t forget, these systems have been trained on existing data from the internet. At best, they build on what’s already out there. At worst, they plagiarise. For example, some AI image generation applications like LensaAI have generated paintings with ‘fake’ signatures on the bottom. For the system to be trained to understand that signatures feature on the bottom of paintings, it must have ingested paintings with signatures on them. Real artist’s work. At what point can the painter claim copyright, ownership or royalties over the content an AI system generates? For LLMs like ChatGPT, how do we know they haven’t been trained on copyrighted materials, such as books? Or that they won’t be in the future? Where does the ownership lie?

The algorithm and control

You’re putting your trust in someone else’s algorithm, like investing all of your resources in Google search. It works, but what happens when the algorithm changes? Brands have gotten their fingers burned in the past with social media. For example, deprioritizing organic reach in an effort to encourage ad spend. With LLMs, you don’t have a high degree of control over the algorithm. That means that, if and when it changes, there could be an impact on the solutions you build with it. We’ve already seen changes to ChatGPT. The more you build your business on it, the more risky it is if the business model changes, or the algorithms change.

The risk of this is directly proportional to the amount you incorporate it into your product. If it’s only used to help build it, but not a component of the final result, then you have the opportunity to tweak and iterate the output. Letting LLMs loose in the wild is where most of the risk is.

Where LLMs and ChatGPT should be used

While it’s impossible to advise on how to use LLMs in a completely risk-free way, it does seem that you can reduce the risk if you use LLMs (or ChatGPT when it becomes commercially available) to help inform the design and creation process of a specific project or task, but not as an active part of the final product. That way, you’d have a ‘human in the loop’ who would use the LLM to generate materials for conversations or creative output and (vitally) check it over, adjust anything necessary, and improve it before it goes out the door. If the LLM becomes unexpectedly unavailable, then the bot you built or the task you’re working on won’t become unworkable.

As we wrote about in our previous post, there are many potential benefits when it comes to using LLMs to design and tune conversational AI systems. Many of them are ‘background’ tasks, rather than customer-facing output.

Of course, this will change, as LLMs continue to improve and change on a weekly basis. But today, these background tasks are the sweet spot and pretty much the only way you can manage the risks, for now.