The UK Government-commissioned Digital Radio and Audio Review has proposed new regulation that would force smart speaker manufacturers and voice assistant providers to guarantee free access to radio stations.

The review, commissioned in February 2020, and published today, October 21 2021, found that smart speakers are used by a third of the UK population and are outselling traditional and DAB radios by 5:1. The review recommends that measures should be taken to ensure that radio stations “… can continue to reach loyal audiences as radio is increasingly listened to via tech platforms rather than traditional radio sets”.

This is incredibly dangerous language to use. Mandating that a certain group of companies should be guaranteed the privilege of free access to attention is the beginning of the end of the open web. Especially when that attention is ultimately monetised through ads, as most radio stations do.

It seems to be a ‘we don’t want big tech to charge us to be on their platforms, but we’d like to be able to charge advertisers once we’re there’ kind of situation.

The report aims to find ways to “protect UK radio stations’ accessibility”, but reads more like the radio industry is attempting to shield itself from the disruption that voice enabled smart devices can bring.

It states:

“A radio device is now seen by consumers as one dimensional, whereas a smart speaker has multiple functions offering both radio and streaming services along with voice-activation.”

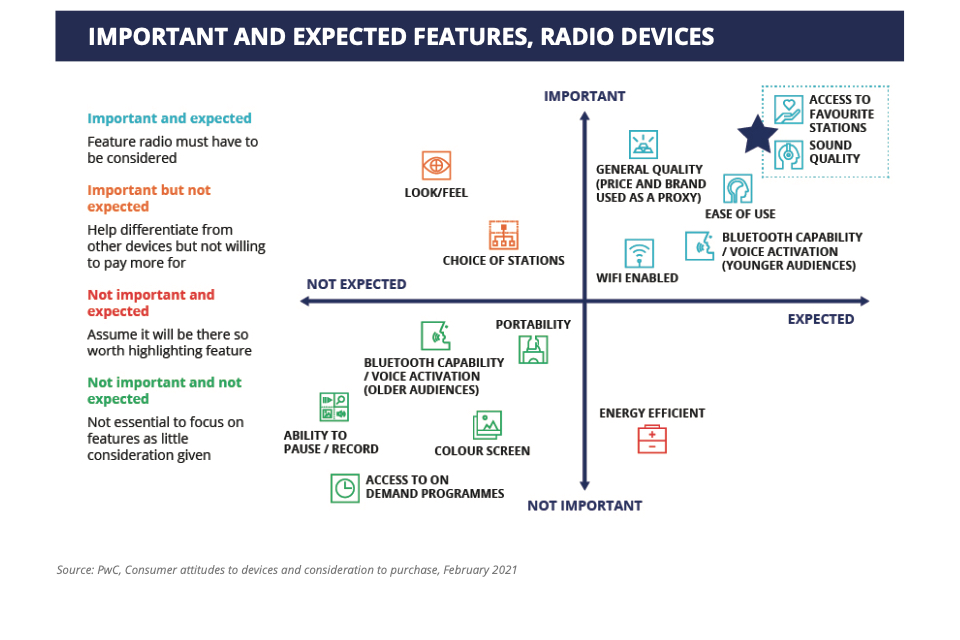

Research in the report from PwC found that, for younger audiences, voice activation is an important and expected factor of a ‘radio device’.

Important and expected features for Radio devices, PwC 2021

But smart speakers aren’t just voice activated radio, as the quote suggests

Smart speakers are an interface to the internet and a myriad of connected services that’s increasing over time. They control your home, manage your schedule, communicate with your friends and family, log your tasks, help you cook, wake you up, heat your car, make your coffee, order you a taxi or takeaway, tell you store opening hours, read you stories and books, answer your questions, play your music and help you get a myriad of other things done with a myriad of other companies and service providers, that are also increasing over time. Oh, you can listen to the radio, too.

The fear of a closed platform

The report cites that 64% of audio consumption on smart speakers is people listening to the radio. And with Amazon, Google and Apple accounting for 95% of the smart speaker market, the report says “… there is nothing within the current regulations to prevent tech platforms from being able to limit or restrict access to UK radio services or to charge stations for carriage”.

The thing is, the same is true for all other internet access points. Most of them are closed to some degree.

Android and iOS provide the gateway to most of the internet. There’s already nothing stopping Apple or Google from charging you to enlist your app.

Most web traffic stems from Google. There’s nothing stopping Google from charging for the right to be listed on Search Engine Results Pages.

A huge amount of internet usage comes from social media. There’s nothing stopping Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and others from charging brands to have accounts.

But they don’t because, although they do intermediate the customer relationship and control the access and attentions of users, they also know that they need to remain open to some degree.

Yes, Google will prioritise your website if you use its ad network. Yes, Apple will take a cut on in-app purchases. Yes, Facebook will charge you to boost your posts. But those companies have built the infrastructure. They’ve taken the risk. They’ve invested their time and capital into their products to create environments where people want to spend their time. And all of that infrastructure will be monetised in some way, otherwise it can’t exist.

Smart speakers are just another version of an operating system, built on the internet. Alexa is more like iOS or Windows than it is a TV set or radio. Therefore, proposing regulation that favours one industry at the expense of another is dangerous.

The report also cites “… neither the BBC nor larger groups have been able to secure satisfactory agreements for access to listening data or prominence for the carriage of their services.”

This is also the case for every other service that runs on the voice assistant platforms. No one gets access to specific data because the data agreement exists between the user and the service i.e. voice assistant. And no one can be guaranteed prominence because that destroys fair competition.

I’m not saying that there aren’t issues with the voice assistant platforms in terms of data sharing, transparency and openness. I’m saying that it’s not specific to the radio industry. It effects everyone building on the platforms.

Stifling innovation

This proposed regulation has the potential to stifle innovation in other areas. Smart speakers offer a completely different way of interacting with content and everyone’s figuring it out. That means there’s fertile grounds for experimentation. Any regulation here means that the radio industry will potentially be standing on the toes of every other company or person trying to calve a piece of this emerging market through innovating in it.

(Edit: in the days following the publishing of this article, two new things were announced. 1. Amazon intending to roll out a platform to enable people and companies to create what it calls the future of radio. 2. On a smaller scale, a startup, Voxprotocol, announces themed radio stations where users can personalise their radio based on their preferences, and an ad model on top. This is the exact innovation that regulation would prevent.)

Shooting yourself in the foot

Regulation like this also has the potential to stifle the innovation within the radio industry itself. If there was regulation guaranteeing free access to radio stations on voice platforms, then what would happen when one of those radio stations decides to offer a subscription service?

That’s what happened with publishers online, as they shifted from ad-driven print formats onto digital. They put up paywalls.

If any radio station wanted to offer premium content behind a paywall, then they’d be commercially benefitting from the regulation at the expense of other industries and content types, which would likely then require its own regulation to prevent. Now you’re wrapping red tape around the internet.

You can’t stop disruption

We’re now in a new age of media where radio, news, music, podcasts, audiobooks, audio articles and all other content is converging. People have a choice about what they listen to, where and how. The radio industry seems to be just realising that it’s now at the mercy of the internet, and it’s trying to regulate its way through it.

New competition

In the same way as the BBC is competing with Netflix, radio stations are competing with things like flash briefings and Spotify. In the same way as Netflix is competing with cinemas, radio stations are competing with podcasts and native-voice content like interactive news, quizzes, games and another interactive content.

We’ve long chronicled the issues with voice platforms and third party app discoverability, which is a problem. But it’s a problem for everyone. Fixing or regulating certain access rights for one group will hinder the innovation, exposure and potential of other groups.

Radio can’t be given any special privileges. That would be like regulating Facebook, so that it has to promote publishers ahead of all other posts. Or regulating Google, so that it has to promote one industry’s website over another.

If the radio industry gets special permission, then why can’t games or finance or retail or any other industry type be granted guaranteed the same? Before you know it, every industry would have special permissions, which negates the need for special permissions and we’d be back to square one. The real question is about openness of the entire platforms.

Disruption has already happened

Other media forms have already been through this disruption, and they were fine (mostly).

It happened to print media

The internet in general disrupted the print industry, forcing traditional news companies to change their ways and innovate. There wasn’t special protection given to news organisations online. There wasn’t regulation proposed that would mean Google has to serve content from specific news providers for free.

The result meant that news organisations had to compete with all other websites for traffic and attention, and had to find new ways of generating revenue.

The internet, as it tends to do, forced publishers into creating new subscription or digital ad-based business models.

It forced them to find out how loyal their readers really were, and how much prior custom was down to limited choice or monopolies.

On a newspaper stand, you had the choice of 20 newspapers. Online, you have 20 billion websites, each specifically honed-in on a particular niche that might interest a reader more.

One could argue that this was the beginning of ‘click bait’ and the origins of fake news and overblown headlines, but you can’t argue about the value of a level playing field in fostering innovation and value.

It happened to TV and film

The same thing happened with the rise of high speed internet. That disrupted the traditional TV and, eventually, the film industry.

The rise of online streaming platforms and a myriad of connected devices to watch them on, from phones, tablets, laptops and smart TVs, took attention away from traditional TV viewing and cinema visits.

We now live in a world where content can be accessed from endless providers and users decide whether to watch Netflix, Disney, Hulu, BBC, YouTube, Twitch, traditional TV, on demand TV or consume content on social media.

There wasn’t special measures introduced to protect access to traditional TV networks online. A mandated right for BBC iPlayer, ITV Hub or 4 On Demand to have free access to iPhone or Android users. Instead, they entered the world of the open internet, the world of free competition.

Misunderstanding the disruptive nature of voice

It doesn’t seem like there’s a full appreciation for the level of disruption voice operating systems can bring over the next 10 years.

Media Minister, Julia Lopez, said:

“We must make sure this treasured medium continues to reach audiences as listening shifts to new technologies and that we have a gradual transition away from FM to protect elderly listeners and those in remote areas.”

Making sure the medium continues as listening shifts to new technologies underestimates the disruptive potential of new technology mediums and the internet in general. Using words like ‘treasured’ shows an emotional connection to the radio medium, but the market doesn’t care about emotions.

Smart speakers and voice platforms are operating systems, not simply new listening or broadcasting channels. Arguably, the radio industry should be innovating ways to remain relevant as technology advances and habits change, not to ‘make sure’ it can ‘reach audiences’ through regulation.

Lopez continued:

“We will not have a digital switchover until at least 2030 and will consider new rules to keep our thriving radio sector at the heart of the UK’s media landscape.”

Arguably, the heart of the global media landscape is social media and the internet. Radio stations are content providers in the same way as TV networks in 2021 are content providers, in the same way that news orgs are content providers. The job that all content providers have is to create great content, first and foremost. Second, is to find ways to distribute that content to people who want it.

The radio industry seems to be viewing smart speakers purely as a new distribution channel, not as a new way of creating new, great content fit for the medium and engaging audiences.

And while its true that the radio played a vital role in bringing news and entertainment to those in need during the pandemic, those that are in need; those that need the radio to be accessible, as Lopez mentions, is the elderly and those in remote locations, who rely on FM transmission.

What’s really going on here?

What’s really going on, it seems, is that the government intend to retire the FM radio network and move all radio to DAB, in the same way as it moved all analogue TV to digital in 2012. The natural decline in FM radio use and natural increase of DAB and internet consumption make it too expensive to maintain FM and AM infrastructure for a few people.

When FM radio is retired (recommended to be 2030, according to the report), there’ll be people who no longer have access to the radio. Those people will be forced to either buy a DAB radio or use another medium, like a smart speaker or other internet enabled device.

“… analogue radio listening will account for just 12 to 14 per cent of all radio listening by 2030, but FM in particular remains highly valued by many listeners, especially those who are older or more vulnerable, drive older cars or live in areas with limited DAB coverage.”

What this hints at, is the assumption that some people might have no choice but to buy a smart speaker (or in-car assistant, like the Echo Auto) to access the radio because the DAB signal might not reach their house or car.

Therefore, the government is continuity planning, and views smart speakers as one of the viable alternatives to FM radio. Again, this fundamentally underestimates the disruptive nature of interactive voice operating systems and the internet in general.

You can’t regulate one area because you’re loosing customers in another. You have to compete with everyone else fairly across all platforms, operating systems and devices.

Welcome to the disruption of the internet

What we’re seeing here is that the traditional radio industry is now facing the disruptive power of the internet and changing customer expectations.

Almost every other industry on the planet has been disrupted by it and had to adapt. At this point, I fail to see what makes radio any different and fail to understand why this industry out of all the others that came before it, should be given special regulatory protection.

While I agree that more needs to be done to encourage openness and data sharing on the voice assistant platforms, I don’t agree that special treatment should be given to any specific industry. It should be open for all.

This isn’t a smart speaker and radio debate, it’s deeper than that

This brings up a wider debate that’s not confined to smart speakers and radio stations. The debate should be around free and open access to the internet on the whole, as more big tech companies control the access points to it, and intermediate customer experiences.

There’s definitely a bigger question to answer about how big tech’s incentive structures might not always align with what’s in the user’s best interest; the impact that has, and the case for a truly open web.

But that’s for another day.